10 min to read

Translation and Types

First, let’s just define some concepts you’ll need to be aware of before reading this article:

- Source Code: The original code the programmer writes, before any translation.

- Run-time: The time period in which your application is running.

You should also have a good understanding of what a type is.

The following three concepts are all very similar, and people get them mixed up all the time, which leads to many developers getting confused. By the end of this article, we’re hoping that you’ll understand all of these concepts and the differences between them.

Translation: Compiled vs Interpreted. When the source code is translated from what the programmer writes, into another language.

Type Checking: Static vs Dynamic. When the types of the application are checked.

Type Safety: Strongly-Typed vs Weakly-Typed.

Compiled vs Interpreted

Before you write an application your first job is to choose a language. There are many languages you can choose from, but almost all share one thing in common; your computer can’t understand them.

The reason I said “almost all” is because there is one language computers can read; machine code.

Machine code is a computer programming language consisting of binary or hexadecimal instructions which a computer can respond to directly.

Although it’s possible for developers to program in machine code, most don’t and instead opt for a high-level language.

The differences between low-level languages and high-level languages could be its own article, but the basic summary is:

- A low-level language is written for one type of architecture (Windows, Linux etc) and won’t work on another. It is more difficult to read and understand but has a higher level of performance.

- A high-level language is basically the opposite. You can write it once and it will run on all, or at least most, architectures. It’s a lot easier for people to read and understand but isn’t as performant.

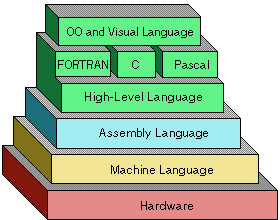

Which languages are high-level, and which are low-level? Every language sits on a spectrum.

Those that are less complex for humans to understand and write, but provide less flexibility over what the programmer can do, are considered high-level. A language at the top of this spectrum could look like this (note: a language this high-level has not yet been created):

Create an application that accepts two numbers,

subtract the second from the first,

return the result.

Those that are more complex for humans to understand and write, but provide much more flexibility over what the programmer can do, are considered low-level. The language at the bottom of this spectrum is machine code, which looks like this:

0x 60 00 00 80

0x A4 00 00 00

0x 60 01 00 84

0x A4 01 01 00

0x 60 02 00 00

0x 60 03 00 04

0x 60 04 00 00

0x 60 05 00 01

0x 08 00 00 02

0x 20 00 00 03

0x 20 04 04 05

0x 11 20 04 01

Somehow the code we write has to be translated into the language that computers can understand (machine code). This is either done using compilation or interpretation.

Compiled

A language is considered to be compiled if the source code is translated before run-time. The compiler will have an input of the programmers’ source code, in its entirety, and an output of the target language (usually machine code).

Sometimes there is an intermediary language, called assembly, if the language can’t compile directly to machine code.

Interpreted

A language is considered to be interpreted if the source code is translated on the fly, during execution. When a piece of source code needs to be executed, the interpreter will translate just that bit of source code into machine code.

At it’s most basic if you need to run the same piece of source code twice, it will need to be converted to machine code twice; which is a waste of resources. However, most interpreters have optimisations to reduce this resource waste.

Why does all this matter?

If you opt to use a language that uses an interpreter, the time from writing/editing the source code to running the application is reduced. Not having to wait for your source code to be compiled could save you a significant amount of time (depending on the size of your project, the compiler and the performance of your machine).

You also won’t need to generate multiple output files, to run on each different architecture. You will be able to run your source code, in the same way, on all architectures and let the interpreter handle the rest.

If you opt to use a language that uses a compiler, it is generally going to be more performant. It won’t have the additional step of having to translate the source code on the fly, because all of the source code would have already been translated.

One final note; just because a language uses an interpreter or compiler, doesn’t mean it can’t use the other. Usually, there will be a standard or accepted method to use, but it is possible for someone to write an interpreter and/or compiler for any language.

Static vs Dynamic

Every programming language has data-types. One reason for this is so computers know what operations can be performed on them.

Imagine we’re writing a function that will take two inputs; subtracting one from the other.

subtract(input1, input2) {

input1 - input2

}

Note I said inputs, instead of numbers. Technically, we could pass anything through to this function

subtract(5,3) // 2

subtract(19,40) // -21

subtract(9,3) // 6

subtract("hello","world") // wait, what?!!

What is "hello" - "world" ? No idea? Why not? Because they are both strings, and it doesn’t make any sense. Exactly!

Computers won’t be able to understand this either, so we need a way of checking to see if we’ve made any of these mistakes.

This can be done using either Static Typing or Dynamic Typing.

A statically typed language will check for these errors before run-time and, if any are found, it will report the problem and will usually prevent the application from running, until the issues have been fixed.

A dynamically typed language will check for these errors on the fly, during execution. Your application could run without ever having a problem, or it could suddenly crash, possibly after days if there is an unexpected error.

Let’s look at an example. The following is the start of our application; we’ve declared two functions, one with the same subtraction error we discussed earlier, and the other with a completely valid subtraction.

subtractionWithError() {

"hello" - "world"

}

validSubtraction() {

9 - 4

}

validSubtraction()

Note how only the validSubtraction function is executed.

If you were using a statically typed language, an error would be shown before the application runs.

If you were using a dynamically typed language, an error would never be thrown because the code with the error ( subtractionWithError ) will never be executed, and your application would continue to run without any idea there’s an error.

What if our code called the validSubtraction function, waited for 4 hours, and then called the subtractionWithError function?

subtractionWithError() {

"hello" - "world"

}

validSubtraction() {

9 - 4

}

validSubtraction()

wait(4 hours) // wait for 4 hours before continuing

subtractionWithError()

If you were using a statically typed language, the behaviour would be exactly the same. An error would be shown before the application runs because, executed or not, it knows there’s an error.

If you were using a dynamically typed language your application would run fine for the first 4 hours but, as soon as the subtractionWithError function is executed, it would then show an error and possibly crash (depending on what the problem is).

Why does all this matter?

Statically typed languages will have better performance at run-time, because the knowledge of types and the confidence that everything has been checked, allows for optimisations that simply aren’t possible with dynamically typed languages.

Dynamically typed languages don’t have to go through the overhead of checking everything prior to run-time, so it’s quicker to go from writing/editing the source code to running the application. Like interpreted languages vs compiled languages, this could save you a significant amount of time.

To summarise:

- Compiled & Statically typed languages - larger overhead to go from writing your source code to running it, but faster at run-time. Different executables for different architectures.

- Interpreted & Dynamically typed languages - much quicker to get your application running from the source code, but slower at run-time. Run the same code for all architectures.

Strongly-Typed vs Weakly-Typed

A strongly-typed computer language is one where the programmer declares in advance what data-type something is.

var x string = "Hello world"

func example(input1 int, input2 int) {

input1 - input2

}

A weakly-typed language is one where the data-type is determined by what is given to it.

var x = "Hello World"

func example(input1, input2) {

input1 - input2

}

Strict typing will help you avoid errors, like the one we saw earlier when trying to subtract strings ( "hello" - "world" ), before we even get to the compilation or run-time stages.

Weak typing allows you to have more flexibility in what you can do. The most strictly typed languages won’t allow you to add an integer to a floating point number, whereas a weakly typed language would allow you to add a string and an integer.

6 + "5" // 65

Just be cautious when using weakly typed languages, you might get unexpected results if you don’t handle type checking yourself (e.g. you think you’re adding integers to integers but you’re actually adding integers to strings.)

Comments